Dazibao (Chinese Big-Character Posters): Voices of Revolution and Social Change. Discover How Handwritten Walls Shaped China’s Political Landscape.

- Origins and Historical Context of Dazibao

- Design, Format, and Symbolism of Big-Character Posters

- Dazibao in the Cultural Revolution: Tools of Protest and Propaganda

- Key Figures and Famous Dazibao Examples

- Impact on Society and Political Discourse

- Suppression, Censorship, and the Decline of Dazibao

- Legacy and Modern Interpretations of Dazibao

- Sources & References

Origins and Historical Context of Dazibao

The origins of dazibao (大字报), or Chinese big-character posters, can be traced back to the early years of the People’s Republic of China, but their roots lie even deeper in Chinese tradition, where public wall writing was used for both protest and communication. The modern form of dazibao emerged in the 1950s as a tool for mass mobilization and political expression, gaining particular prominence during the Hundred Flowers Campaign (1956–1957), when citizens were briefly encouraged to voice criticisms of the government. However, it was during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) that dazibao became a defining feature of Chinese political life. Mao Zedong himself famously endorsed the use of dazibao, seeing them as a means for the masses to participate directly in political struggles and to expose “class enemies” within society and the Communist Party Encyclopædia Britannica.

Dazibao were typically handwritten in large Chinese characters on sheets of paper and posted in public spaces such as schools, factories, and streets. They served as vehicles for denunciation, debate, and the dissemination of revolutionary ideas. The posters played a crucial role in the escalation of the Cultural Revolution, as rival factions used them to attack opponents and rally support. The proliferation of dazibao reflected both the chaotic energy and the grassroots participation that characterized the era. Their historical significance lies not only in their immediate political impact but also in their embodiment of the volatile relationship between state power, popular expression, and social upheaval in twentieth-century China Library of Congress.

Design, Format, and Symbolism of Big-Character Posters

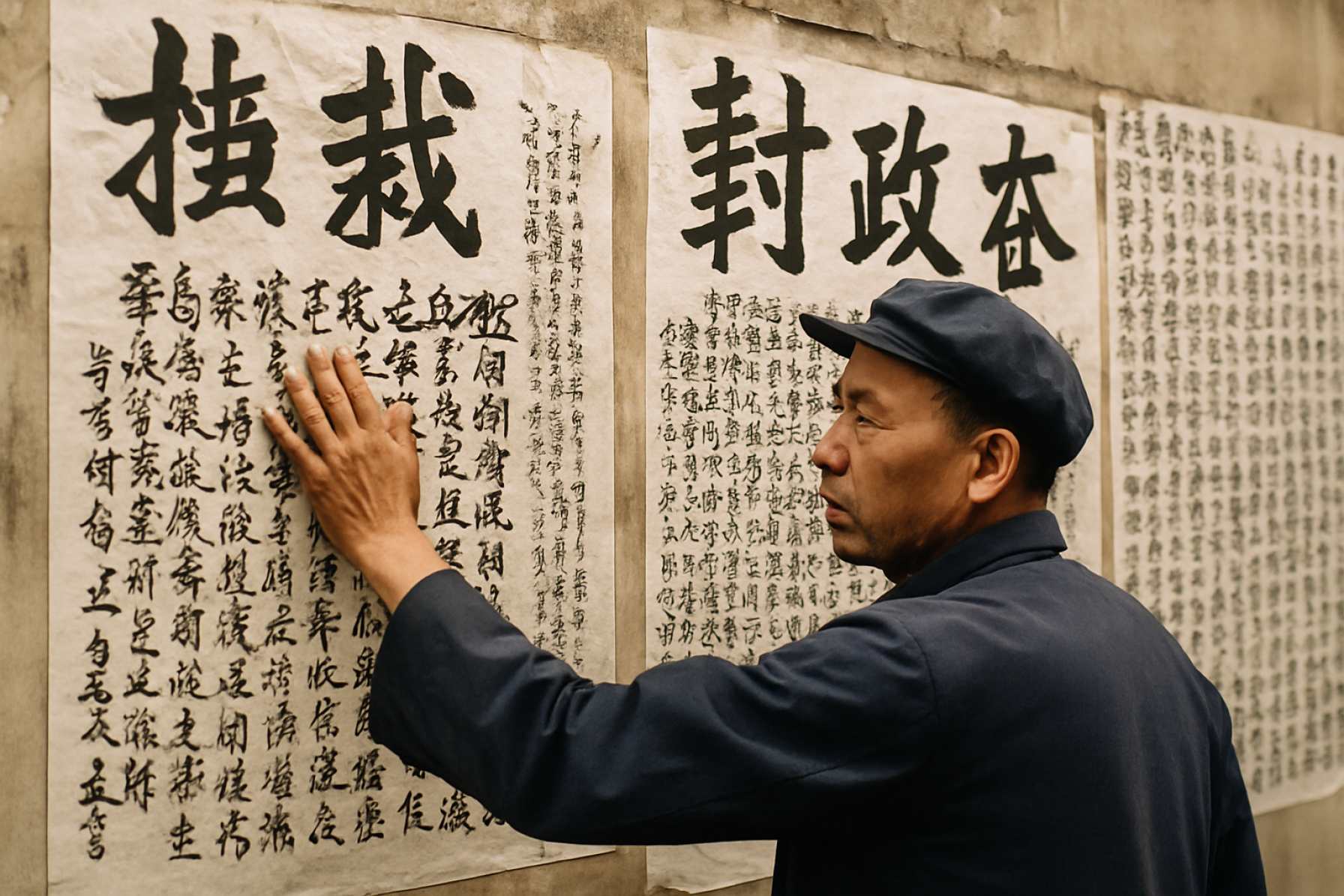

The design, format, and symbolism of dazibao (big-character posters) were integral to their function as tools of mass communication and political mobilization in 20th-century China. Typically, dazibao were handwritten on large sheets of paper, often using black ink and bold, oversized Chinese characters to ensure visibility and impact. The choice of brush and ink was deliberate, evoking traditional calligraphy while simultaneously subverting it for revolutionary purposes. The posters were usually affixed to public walls, school gates, or factory entrances, transforming everyday spaces into arenas of political discourse and contestation.

The format of dazibao was direct and confrontational. Headlines were written in especially large characters to capture attention, followed by the main body of text, which could include accusations, denunciations, or calls to action. The language was often emotive and polemical, designed to provoke strong reactions and mobilize collective sentiment. Red ink or paper was sometimes used to symbolize revolutionary fervor and allegiance to the Communist Party, further enhancing the posters’ visual and ideological impact.

Symbolically, dazibao represented the voice of the masses and the democratization of political expression, at least in theory. Their public display and participatory nature allowed ordinary citizens to challenge authority and shape public opinion. However, the posters also became instruments of intimidation and social control, as their accusatory tone and public visibility could incite mass campaigns against targeted individuals or groups. The visual and rhetorical elements of dazibao thus encapsulated both the emancipatory and coercive dimensions of political life during the Maoist era Encyclopædia Britannica Library of Congress.

Dazibao in the Cultural Revolution: Tools of Protest and Propaganda

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), dazibao—large handwritten posters—emerged as potent tools of both protest and propaganda in China. Initially, these posters provided a rare platform for ordinary citizens, students, and intellectuals to voice dissent, criticize authorities, and expose perceived enemies of the revolution. The movement’s early phase saw dazibao as instruments of grassroots activism, exemplified by the famous poster by Beijing University professor Nie Yuanzi, which criticized university administrators and catalyzed mass mobilization (Encyclopædia Britannica).

As the Cultural Revolution intensified, the Chinese Communist Party, under Mao Zedong’s leadership, actively encouraged the use of dazibao to foment class struggle and denounce “counterrevolutionaries.” The posters became ubiquitous in public spaces—schools, factories, and streets—serving as both a means of mass communication and a weapon for political persecution. Dazibao were used to publicly shame individuals, spread revolutionary slogans, and incite collective action, blurring the line between spontaneous protest and orchestrated propaganda (Library of Congress).

Over time, the state’s manipulation of dazibao contributed to an atmosphere of fear and conformity, as people competed to display their revolutionary fervor and avoid suspicion. While dazibao initially symbolized popular empowerment, their widespread use ultimately reinforced the Party’s control over public discourse, illustrating the dual role of these posters as both vehicles of protest and instruments of state propaganda during the Cultural Revolution (The China Quarterly).

Key Figures and Famous Dazibao Examples

Dazibao, or big-character posters, became a powerful tool for public expression and political mobilization during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Several key figures played pivotal roles in both the creation and dissemination of influential dazibao. One of the most famous examples was penned by Nie Yuanzi, a philosophy lecturer at Peking University. In May 1966, Nie’s dazibao criticized university authorities for suppressing revolutionary fervor, an act that received direct endorsement from Mao Zedong and is widely regarded as the spark that ignited the mass movement of the Red Guards.

Mao himself was a central figure in the dazibao phenomenon, not only encouraging their use but also authoring his own. His famous poster, “Bombard the Headquarters,” called for attacks on the Communist Party’s leadership, further fueling the chaos and radicalization of the period. Other notable contributors included Chen Boda and Jiang Qing, who used dazibao to target political rivals and consolidate power.

Famous dazibao were not limited to elite figures; ordinary citizens and students also produced posters that became widely circulated and discussed. These posters often featured bold, accusatory language and were displayed in public spaces, serving as both a means of protest and a method of mass communication. The legacy of these key figures and their dazibao continues to shape the historical memory of the Cultural Revolution and the role of public discourse in modern China.

Impact on Society and Political Discourse

Dazibao, or Chinese big-character posters, played a transformative role in shaping both society and political discourse during key periods of modern Chinese history, most notably the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). These handwritten posters, often displayed in public spaces, became a primary medium for ordinary citizens, students, and political actors to express opinions, criticize authorities, and mobilize collective action. The public nature of dazibao fostered a culture of mass participation, enabling individuals to bypass traditional hierarchies and directly challenge officials or policies. This contributed to a climate of intense political engagement, but also to widespread social upheaval, as accusations and denunciations could rapidly escalate into campaigns of persecution and violence Encyclopædia Britannica.

The impact of dazibao extended beyond immediate political campaigns. By democratizing the means of communication, dazibao temporarily eroded the monopoly of the state-controlled press, allowing for a plurality of voices—albeit within the shifting boundaries set by the political leadership. However, this openness was double-edged: while it empowered grassroots activism, it also facilitated the spread of rumors, personal vendettas, and factional strife. The posters became both a tool for social critique and a weapon for political struggle, reflecting and amplifying the volatility of the era The China Quarterly.

In the long term, the legacy of dazibao is complex. While their use declined after the Cultural Revolution, the memory of their power to shape public opinion and political outcomes continues to influence Chinese approaches to dissent and information control Library of Congress.

Suppression, Censorship, and the Decline of Dazibao

The trajectory of dazibao, or Chinese big-character posters, was profoundly shaped by state intervention, particularly as their use became increasingly politicized and destabilizing. Initially encouraged during the early years of the Cultural Revolution as a tool for mass mobilization and criticism, dazibao soon became a double-edged sword. Their unrestrained proliferation led to factional violence, personal vendettas, and challenges to Party authority. By the late 1960s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began to view dazibao as a threat to social order and its own legitimacy. In response, the state implemented strict censorship measures, curtailing the public display and distribution of these posters. The Central Committee issued directives to limit the content and scope of dazibao, and by the early 1970s, their use was largely restricted to officially sanctioned criticism or propaganda.

The decline of dazibao accelerated after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The 1980s saw a brief resurgence during the Democracy Wall Movement, when citizens used dazibao to call for political reform. However, the government quickly suppressed this movement, dismantling the Democracy Wall and arresting key activists. Subsequent legal reforms, such as the 1982 Constitution, explicitly prohibited the use of dazibao for unauthorized public expression, cementing their decline as a medium for dissent (National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China). Today, dazibao are largely relegated to historical study, their legacy serving as a reminder of both the power and the peril of unfettered public expression in modern China (Encyclopædia Britannica).

Legacy and Modern Interpretations of Dazibao

The legacy of dazibao (big-character posters) extends far beyond their original function as tools of mass mobilization and political expression during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. In the decades since, dazibao have come to symbolize both the power and peril of grassroots communication in authoritarian contexts. Their historical role as vehicles for public criticism, denunciation, and debate has been reinterpreted in contemporary China and abroad, often serving as a cautionary tale about the volatility of mass movements and the dangers of unchecked populism. Scholars and artists alike have revisited the dazibao phenomenon, analyzing its impact on collective memory and its resonance in modern protest culture Encyclopædia Britannica.

In modern China, the spirit of dazibao occasionally resurfaces in digital forms, such as online forums and social media, where citizens voice dissent or mobilize support for causes—albeit under strict state surveillance and censorship. The visual and rhetorical style of dazibao has also influenced contemporary Chinese art and activism, with artists appropriating the format to comment on current social and political issues Tate. Internationally, the concept of the big-character poster has inspired protest tactics in other societies, highlighting the enduring appeal of direct, public communication as a tool for social change. Thus, while the original context of dazibao is rooted in a specific historical moment, its legacy continues to inform debates about free expression, collective action, and the politics of memory in the 21st century The China Quarterly.